This past month has been one of the most difficult for us all — in our jobs, life, and social groups. I want to share my story about how I am juggling research, teaching, and the pandemic during these uncertain times.

I have spent the last month hiking rock outcroppings and grasslands of Los Baños Grandes, on the east side of the inner Coast Range of California. I went solo, not only to avoid the COVID-19 outbreak in densely populated cities, but also to catch lizards and study the Rock-Paper-Scissors game theory. I have been catching a variety of lizards for my research around Los Baños Grande each spring for more than 32 years now. But beyond my long standing research, I have two other goals here in the desert, remote field-based teaching and an important conservation project.

Goal 1: Rock-Paper-Scissors

My first goal involves the evolutionary ecology of the well known Rock-Paper-Scissors (RPS) game theory. Remember the hand game from your youth where Rock blunts Scissors, Paper wraps Rock, and Scissors cuts Paper? The RPS is played in real life by lizards. The theory for RPS is changing our view of species stability, behavior, and the source of diversity across ecological systems as I discussed in this Quanta Magazine article.

I have been so busy catching lizards this month for the 31st generation of RPS that I missed this article. https://t.co/CAZkM8UMeu

— Barry Sinervo (@BarrySinervo) April 14, 2020

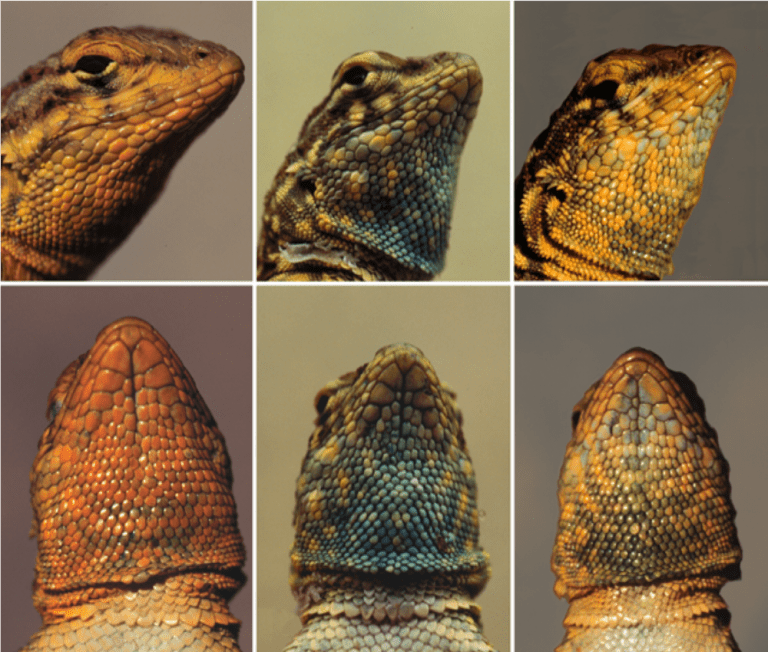

Why study a system for 32 years? Well, RPS cycles are rapid. In lizards, the gene for the RPS game is color-coded on the throats of males and females, making them easy to see. For example, it takes only four years for a lizard’s color to go from orange (Rock) to yellow (Paper), yellow to blue (Scissors), and then blue back to orange — the most regular ecological cycle on Earth. Female color types drive an even more rapid 2-year cycle of high and low color density.

This is particularly interesting because I discovered that the color of a lizard determines their behavior. At Los Baños, male lizards with blue throats will give up their lives defending a blue neighbor against more aggressive male lizards with orange throats — this is the first example of genetic altruism in a vertebrate. The same RPS math for the cooperation and care behaviors of mammals governs their social systems.

Still, even after the 32 years it took for me to understand the evolution cycles of lizards and the causes of ecological stability, things are changing and new details are arising.

This year female lizards had the earliest egg lay date since I started in 1989. Why? Well, it didn’t rain from January to February, allowing the lizards to sit under the sun and breed early. Lizards love the sun. So do snakes, which means more snakes were abound and started eating the lizards earlier. The result makes 2020 the lowest population density year ever, with only 150 lizards across 10 study populations, compared to the highest density year of 4,600 lizards in 2008.

Goal 2: Remote field-based teaching

This leads me to my second goal of teaching a Herpetology Field Class for spring quarter, or “herps” — a field course in which students can catch, hold, and study amphibians and reptiles, just like those found at Los Baños. This was quite a conundrum for me. How on Earth do I teach this hands-on activity in the virtual learning environment of Zoom? I realized I had to become a videographer and enlist the aid of fellow “herpers” (Regina Spranger, my TA; and Alex Jones, Alex Krohn, and Joe Miller who work in the UC Santa Cruz Natural Reserves). This past month, we harvested natural-history videos of reptiles and amphibians to keep students engaged, and inspire the students to save the herps of California — now endangered by climate change.

Goal 3: The “conservation bank”

I have been working on endangered species assessments for Donn Campion, the landowner of Agua Fria Ranch, next to Los Baños Grandes. Donn set up a “conservation bank,” a large proportion of personal property that is set aside (in perpetuity) to conserve habitats and help species in plight. Developers of other land can pay into Donn’s Agua Fria “conservation bank” to offset habitat reduction and build an endowment for species protection. Studying at-risk species on personal property is a new research area of economics for me.

I spent a month at Agua Fria Ranch, catching lizards during the day and surveying biodiversity at dusk. During dusk surveys, I saw burrowing owls, kit foxes, tri-colored blackbirds, and loggerhead shrikes, and I found California tiger salamander larvae in ponds. We know of at least five desert kit fox families on the northern half of Donn’s 3,600 acre property. We still need to study the southern half to see if there are similar numbers. Ten would be an amazing number of kit fox families on 3,600 acres. We know of dozens of burrowing owl pairs — so many it is difficult to count them. We will try, next year. Tri-colored blackbirds are not yet known to breed on Agua Fria, but we could create new breeding sites for them. I have mixed emotions about helping shrikes. They skewer lizards on barbed wire, but I could study these lizard predators. We can build more breeding ponds for California tiger salamanders (CTS).

A long-term goal is to get Agua Fria greater protection and perhaps add it to the University of California Natural Reserve System (UCNRS) — it is a biome not yet in the UCNRS portfolio: uplands habitat of the San Joaquin Desert ecosystem. I can’t wait to get out even earlier next year, if I can get permits to work on CTS by December 2020. If so, Donn and I could enhance habitat for CTS, and create new vernal pools to protect it and other species in trouble from agricultural development on the floor of the Central Valley. Agua Fria turns out to have a nice climate-change portfolio as well, at 900’ in elevation. My models show many at-risk taxa on the valley floor will have a climate refuge at Agua Fria. Did I mention that Tule Elk roam across Agua Fria? Amazing life out there.

With a conservation bank in place and Agua Fria in the UCNRS future generations of UC students will be able to come out and study the amazing flora and fauna of a unique California ecosystem, the Uplands San Joaquin Desert. There they could study their chosen research organism, maybe even digging deeper into the genome of the side-blotched lizard to map the genes for cooperation and altruism that drive the RPS.

I hope all of you are surviving shelter-in-place orders, my shelter-in-place had the added benefit of some amazing views.

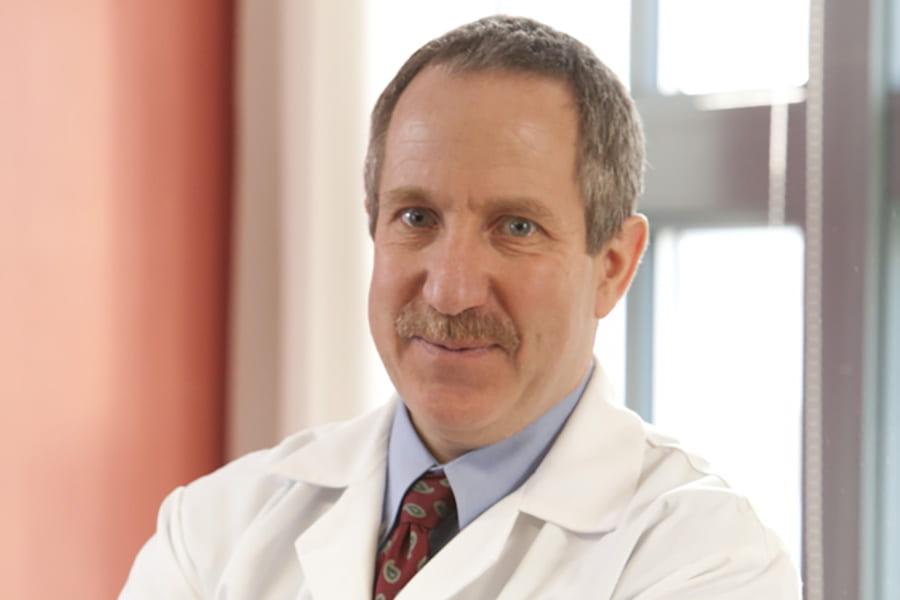

Barry Sinervo is a Professor of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology at the University of California, Santa Cruz. As a mathematical biologist, he led landmark studies of the side-blotched lizards. He showed that the intransitive competitions between the various males creates a cycle of dominance in which each of the three coexisting forms is on top for a year or two.